|

Summer season comes late to the area and leaves it early. The month of May still sees snow storms howling in the tundra and the mountains, and it is only in June that warm days come. The snow mainly melts only by mid-June, while in deeper gorges it remains until next winter. And the local winter returns quickly. In early September the tops of the crests are covered with white snow. Only two months are left for summer: July and August. But it may also snow within this period.

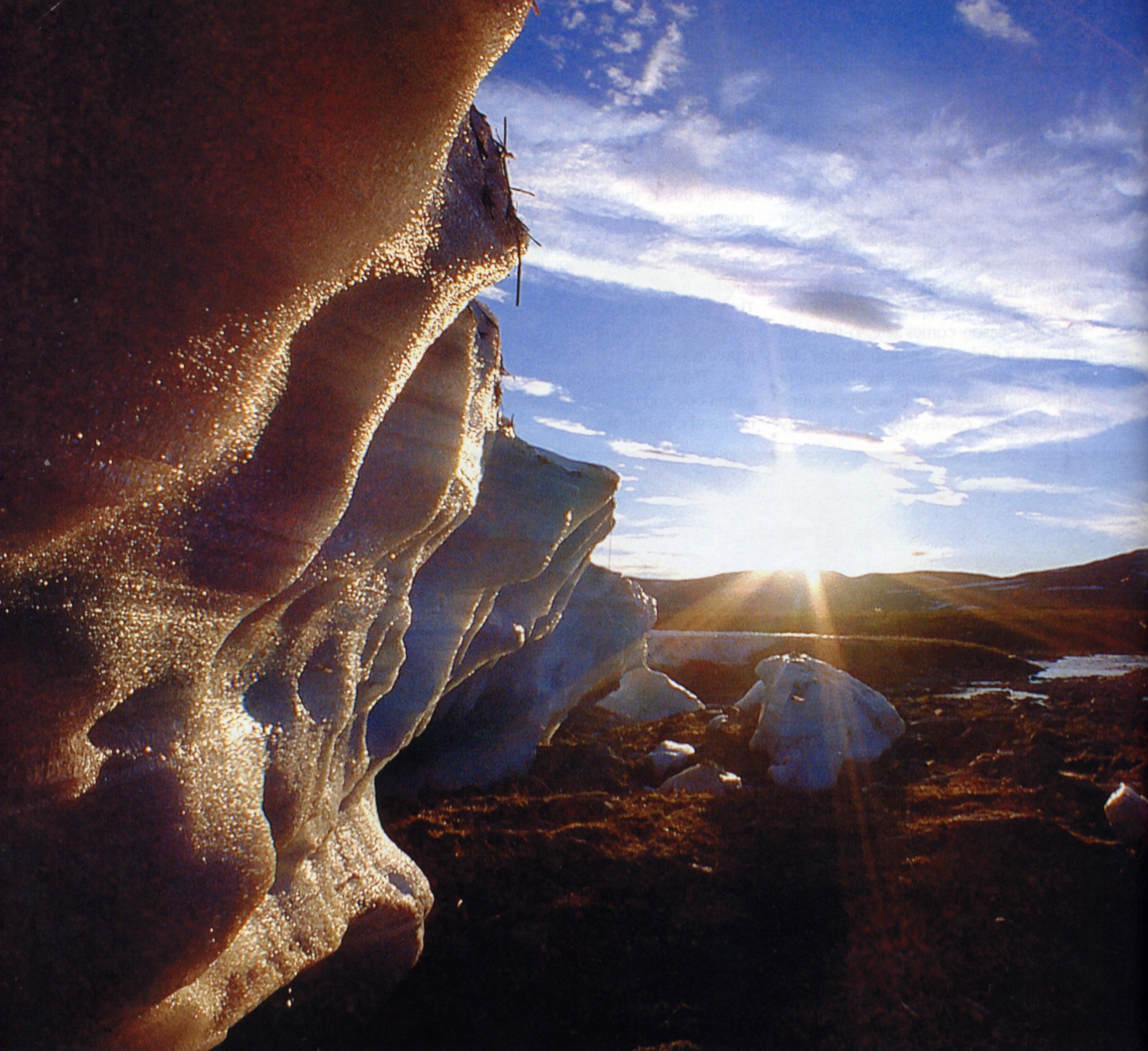

Just make your way to Moscow's Yaroslavsky Railway Station and buy a ticket from Moscow to Labytnangi — the trains set off late in the evening. You may find your first night in a stuffy carriage not much different from previous ones. But you will not even see your second night. By then, in effect, you will have gone far into the North, where in summer the nights are 'white nights'. The following day in the afternoon, you will have crossed the Arctic Circle — with the range of the Urals gradually approaching on the horizon. Soon you will find yourself amidst the mountains. The European-Asian borderline sign will then flash by — saying you are no longer in Europe, but in Asia. In principle, you have already reached the destination. You have now only to choose where to get off. My advice would be Polyarnaya (Polar) station, immediately after crossing the European-Asian border. There is a good earth road leading from the station to the north along the valley of the Big Paipudyna River. Having walked a few hours along the road, you will already find yourself in a wild nature preserve. You are now in the Urals, in the far northern part of the range, which is referred to as the Arctic Urals in geography. Being one of the most mountainous areas within the range, its summits are from 1,100 to 1,300 meters above sea level. It is general knowledge that the Ural Mountains are rounded — owing to their great age. In the Arctic Urals, however, you may come to doubt this. The surrounding landscape reminds one of the Alps. The plants and animals hurry feverishly to use the short summertime. As soon as the snow melts, the ground is covered with a multicolored carpet of herbs and flowers. The local inhabitants, however, do not like the period very much. The reason for this is the innumerable masses of mosquitoes and blood-sucking flies that come up trying to snatch their own share of the natural bloom. The period is not very good in terms of shooting or fishing either. The shooting season opens towards the end of August. By that time there ripen wild-growing berries, and mushrooms grow as well. They say, one needs many pails to gather bog and red whortleberries, cranberries, and cloudberries in the local forests. But nonetheless summer is summer any-way. The local summer is incomparable to its counterpart in central Russia. Everything appears to be so different that you often feel as if you were on another planet. It is not only the sun that never sets: you just lose the usual sense of time, as if you were in a new dimension. Gradually you fall out of your normal daily routine: you feel sleepy in the daytime, and become restless during the night. It is at night, too, incidentally, that blood-sucking flies are a little less active. The bluish radiance of ice buildups will not disappoint anyone! You come across this in many northern rivers. They form in places where a river is shallow, and a river channel is comparatively wide. At the beginning of winter a river gets frozen first of all in such places, making a kind of hanging dam that blocks the river's flow. But flowing water is the kind of force that will always find its way. Forcing its way through to the surface of the dam, it turns immediately into ice. A large multilayer accumulation of ice is thus formed over a winter. The summer is too short to give the sun an opportunity to melt the entire ice formation, which is strengthened from below by numerous cold springs and permafrost. The sunshine and rains perform the work of a sculptor, the shapes of the ice buildups changing daily, strikingly unusual in form. On a clear sunny day, a kind of cold bluish luminescence emanates from them. And as soon as the sun sets closer to the horizon, there appears a thin haze creeping along the valley. As you proceed further to the north along the ridges, there appear more wonders: numerous rivers, beautiful lakes, and even glaciers. There is, by the way, the Urals' deepest tectonic lake, Bolshoye Shchuchye, 136 metres (446 feet) deep. Humans have inhabited the region since ancient times. For centuries, the Nenets people have pastured their rein-deer there. Nowadays you can also come across the reindeer-breeders' houses, chooms, and reindeer herds roaming from place to place. And in the days of old, the enterprising inhabitants of Novgorod were attracted to the land insofar as it abounded in fur-bearing animals and fish. As early as in the 11th century, they would travel along the Pechora and its tributaries, doing trade with the lands behind the Urals. They would go up to the Pechora's tributaries, and then portaged towards rivers within the basin of the Ob. But the absence of direct waterways made the opening and colonization of the region a slow process. With the unification of the Russian lands around Moscow in the 16th century, the exploration of the region was intensified. At that time the state became involved in the process. In 1552 Tsar Ivan IV gave the order "to survey the land and make a draught of the whole state of Muscovy." Within the next 30 or 40 years, large cartographic and descriptive material was accumulated. The Draught of the Whole State of Muscovy, which later was lost, was created on the basis of this material. Such rivers as the Usa, the Pechora's tributary, and the Sob, the Ob's tributary, were already plotted on those maps. The first consistent geographic description and the first map of the Arctic Urals were made after its territory had been explored by the Geographic Society's expedition between 1847 and 1850. The geographic explorations of the time were rather one-sided as their object was to search for waterways connecting the Pechora River and the Ob River across passes in the Arctic Urals. The truly intensive exploration of the region began, alas, at the time known as a gloomy period in Russia's history. In the 1930s, they discovered a very rich deposit of coal at the Vorkuta River. Thousands of Stalin's labor camp political prisoners were forced to build towns and railways in the region. It was they who built the railway between Seida and Labytnangi. They went on building a railway still further, too. Following the death of Stalin, however, the railway construction was discontinued. Nowadays, many kilometers of rusting rails are a reminder of the times. The times now are different, fortunate-ly, and thanks to the railway the Arctic Urals is just a beautiful region of the Russian North, easily accessible, having preserved all the features of a wild nature preserve free from the corruption of civilization.

By Sergey Arpukbin (“Moscow today and tomorrow” September. 2002)

|

If, in the midst of summer,

you come to realize one day that you can no

longer stand the dusty heat and the stuffy air of Moscow; if you

suddenly have the feeling that those huge masses of buildings threaten

to overwhelm you from above, and the burning hot asphalt is swallowing

you up from below; if you strongly feel like taking a good deep breath

of cool fresh air somewhere and changing the scene altogether, then

don't waste time.

If, in the midst of summer,

you come to realize one day that you can no

longer stand the dusty heat and the stuffy air of Moscow; if you

suddenly have the feeling that those huge masses of buildings threaten

to overwhelm you from above, and the burning hot asphalt is swallowing

you up from below; if you strongly feel like taking a good deep breath

of cool fresh air somewhere and changing the scene altogether, then

don't waste time.